“Market depends on people’s judgement of what others are thinking about” – John Maynard Keynes

Many still accuse economists for the Stock Market Crash of 2009, arguing that economists must have used a normative approach to warn ordinary people about the imminent threat and to advise politicians on precautionary measures to be taken. There is always however something unexpected that might occur so irrationally. In 1921, Frank Knight, the great American economist mentioned in his book “Risk, Uncertainty and Profit”, that if you estimate for example say 20% profit probability and you have mathematically proven that, it sounds scientific and so must come true; but who knows what the future holds!

The question is though, how can sometimes every calculation go wrong? What causes the markets to divert dramatically?

It is for sure not an easy question to respond to. However, there is research done, proposing that one of those factors that can shift common markets with high participation very greatly, is the flow of narratives and storytelling. If you wake up tomorrow and see a notification on your phone from Telegraph that experts anticipate a crash in the housing market, and you wanted to sell an asset like a house, what would you do? You will logically avoid selling it until the market becomes normal or you may panic and sell it soon if you believe this crash is lingering. If you choose not to sell that may be a safe choice for the market, but if you decide to sell your house quickly and be “smart”, you and others like you might bring the crash yourself. It is possible that even the anticipation had been wrong, but now by a sudden rise in supply, prices come down and the crash may generate itself! This is how a false narrative can change everything in only one example.

Narratives have long been a major contributor to the markets and their fluctuations. They are so influential in our decision making every day, but we do not notice their significance. Mr. Pigou, in his book, “Industrial Fluctuations” sets out that nearly one third of the causes of changes in our economy are psychological and not monetary nor real. So this is essential to be addressed and talked about in academic environments, though narratives are the least words used in economics and finance fields.

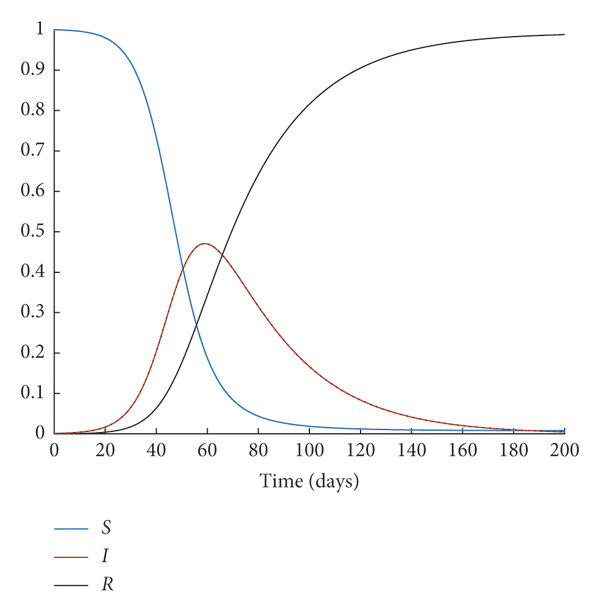

As the understanding of narratives seems so vital, there have been attempts to invent models for them. One great model rectified by Robert Shiller, Yale economist to show the effect and period of a narrative, is a version of an epidemic curves, called SIR model devised firstly in 1927. This invention was to simply represent a projection of a pandemic widespread, but Robert Shiller uses it for the purpose of narratives in going viral. In fact, he compares diseases to stories as they both come one time and will be forgotten another time.

Credit: Wiley Online Library

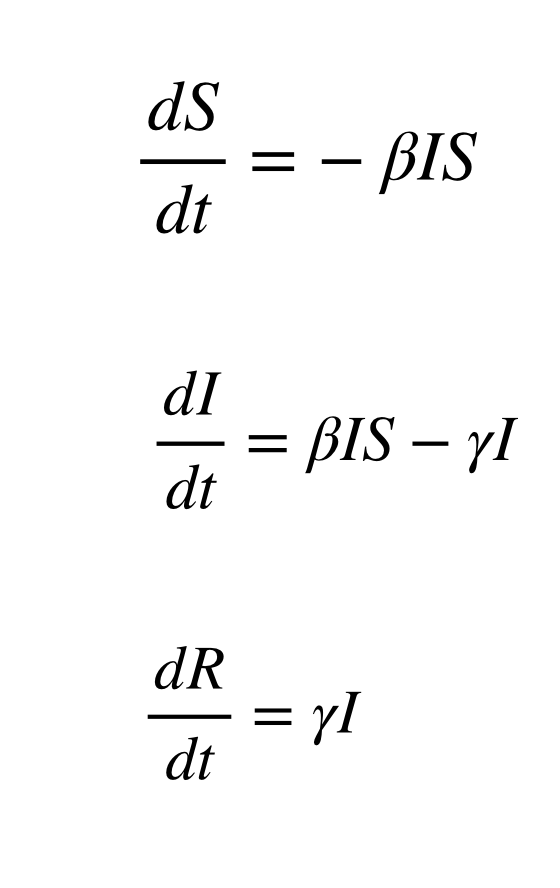

In the figure shown above, I stands for Infected people, S for Susceptible people and R for those Removed or Recovered. In the case of economic narratives, Susceptible individuals are those who have not heard of a narrative but are likely to hear them as their contacts know the narrative. Infected ones are those who are aware of the narrative that is going viral and removed ones are those who have forgotten the narrative. The equation for each curve is indicated below.

Dr. Shiller defines “B” as a constant for virality of attractiveness of the narrative and “r” as the forgetting of the narrative. Therefore a simplistic interpretation of this can be that, as susceptible people interact with infected people, they also become infected to the narrative and the level of their infection depends on the attractiveness of that narrative. Those infected, gradually will forget about the narrative and the level of their recovery depends on how fast or slow they can forget the story. Finally those removed/recovered, can again get into the cycle but for now, they have no attention to the narrative and their decision making does not associate with that narrative.

Now, what is the problem?

The problem is that, despite the inter-disciplinary works done and the growing knowledge of this area, we are all dependent on narratives more or less, while we cannot control them.

We talked about the attractiveness and forgetting of narratives, now what drives them the most? One reasonable answer is their importance. How do we know something is important or not? By a lot of factors such as our rational thinking, books we read, TV and much more sources, however still the most influential source can be named as our social media. Who controls social media? Roughly no one. It is an agglomeration of people and companies and it is free to share your thoughts on that and your power is not limited by any external forces. Also, it means that there is a mass of news out there that is being mediated the moment after the occurrence and so news become less igniting. This means that the cycle of SIR curves, will be packed and repeated thousands of times everyday. You hear news, become interested and forget about them the moment after. What this can bring about, is a sense of carelessness and absolute indifference. If there is a market crash tomorrow and experts warn it but you do not care, the market will automatically crash.

In addition, if there is no control over the narratives, they might fluctuate the market and no business will win because the decisions are not based on prices, but on narratives. The market becomes increasingly volatile, the incentives for entrepreneurial works decrease and it might lead to a lack of innovation potentially.

Thus there should be a way of controlling narratives even if that is very little. As the transmission of information become faster and easier ever since, the fluctuations can reach higher levels that is not favourable. There are numerous organisations and universities researching on this as of now, and in our association we are also doing the best we can to find a solution to it. Nevertheless, the impact of narratives in economics is undeniable.