Increasingly, in the past couple of years, I find myself walking down the aisles of my local Tesco ever more morose. The milk that I once bought at £1.15 is now £1.65. Pasta, washing-up liquid, even the basic loaf is now 10-30% higher than I initially remember. Nothing else about the shop has changed: same shelves, same suppliers, same cashier. Something is off. The narrative that was presented to us in 2021-2022 was tidy: “too much money chasing too few goods”, with excess demand and supply-chain bottlenecks being the purported prognosis. But as you keep shopping – week after week – you start to notice that prices have not only risen in tandem with costs; they have now far exceeded them and stayed there. Not scarcity, then, but strategy I thought.

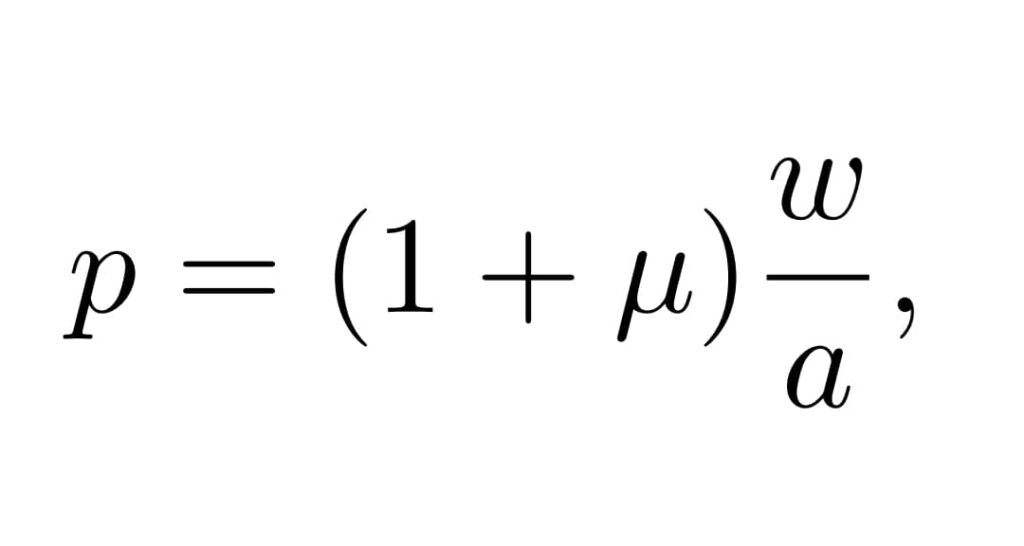

Milton Friedman’s famous line – inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon – is rhetorically elegant but empirically cramped. It does not explain the real world dynamics underlying these price rises – presenting an overly simplistic view. A more sophisticated lens comes from Michał Kalecki’s price-setting theory: in concentrated markets, firms set prices as a markup over unit costs. In its simplest form:

Where ‘p’ is price, ‘mu’ is the markup, ‘w’ is the money wage, and ‘a’ is the productivity of labour (output per worker). So when wages go up or productivity drops, prices rise – but more often than not, it’s just companies jacking up prices because they can. Markups are simply the amount that businesses add on top of the cost to produce one unit of a good – this is what allows them to generate a profit. Thus, the equation provides us with a more vivid picture of the real-world variables that control the underlying inflation. This gives us a solid place to start, so we can begin to disassemble the economic machine and identify the truth behind the price tags. Interestingly, although somewhat obvious in hindsight, markups are an important driver of inflation and are traditionally absent from analysis of inflation presented in the media. To illustrate, the Financial Times (FT) published an article in 2022 in the midst of the inflation crisis, attributing inflation to all the usual culprits: supply shocks and wages, excluding the elusive markups. Although partly correct, the omission of markups is not innocuous – it has clear policy implications and, if deliberate, risks amounting to political scapegoating. By narrowing people’s attention to wages and supply bottlenecks, this framing insulates corporate pricing power from scrutiny and steers the effective policy response altogether. Hence, by adopting Kalecki’s framework, we move from narrative to evidence on the sources of inflation.

When we apply this framework to the pandemic and its aftermath, the prevailing paradigm seems distasteful. Yes, supply shocks and energy costs mattered; yes, wages moved in some sectors. But a striking part of the inflation story is profiteering: large firms leveraging economic turmoil to expand margins and push up prices. As Isabella Weber argued early in the surge, 2021 saw an “explosion in profits” – US non-financial profit margins rose to levels not seen since the aftermath of World War II – consistent with companies seeing what they can get away with rather than mere cost pass-through.

One reason the “excess liquidity” narrative also misleads is that it assumes a near-uniform drift in prices. Blair Fix shows the opposite: since 2020, the cross-sectional variance of CPI items has broadened significantly. The variation in price changes was often larger than the average itself – exposing a pattern of winners and losers that points to power and restructuring, not a homogeneous money tide. If inflation were purely a monetary phenomenon, you’d expect a degree of synchrony. Instead, we saw dispersion consistent with sectors exercising markups where they could. Providing us with even more evidence that firms are altering markups. After being exposed to these arguments, you begin to wonder if there is more to the story than we are being told, and if markups truly play a bigger role than we are being led to believe.

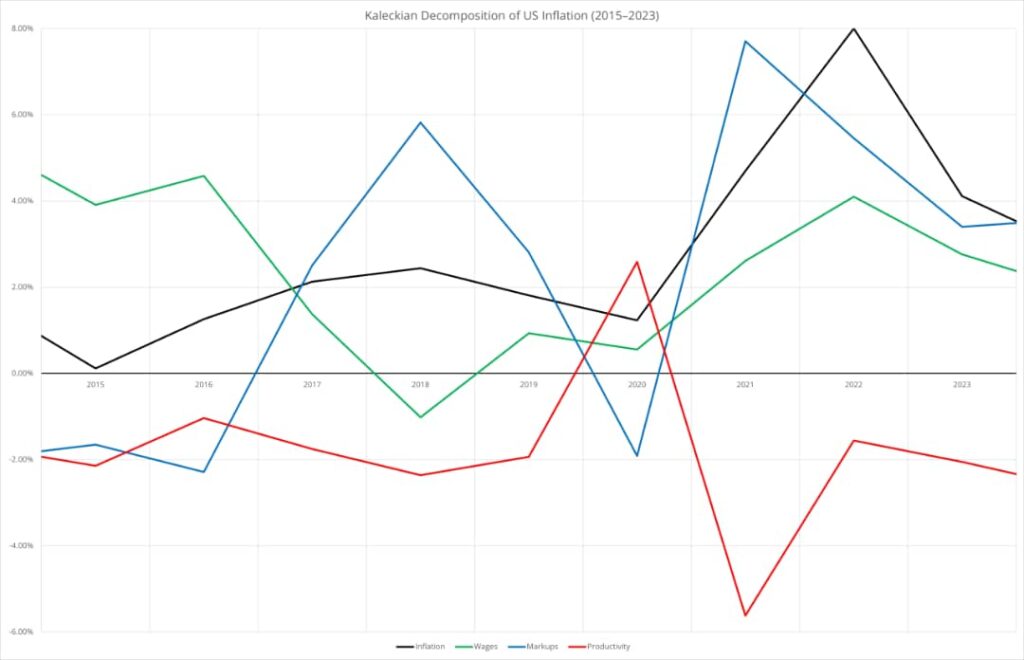

Thus I did the analysis, using a method Steve Keen applied to US data – reproducing the graph for the US and new graph for the UK. Below is the Kaleckian price-setting decomposition of inflation in both the UK and US:

Notes:

UK: Inflation: Annual growth rate of CPI Index; Wages: Annual growth rate of seasonally adjusted regular pay excluding arrears; Productivity: Annual growth rate of output per hour worked for whole economy, Chained Volume Measure (CVM) Index; on the chart I plot the negative of the productivity growth rate so that higher productivity appears as a downward contribution; Markups: Calculated as a residual using the equation:

US: Inflation: Annual growth rate of CPI Index; Wages: Annual growth rate of compensation for production workers; Productivity: Estimate using annual growth rate of real GDP per capita (chained dollars) – not perfect, but close enough; Markups: Calculated as a residual as above.

Across 2015-2023, the decomposition in Figure 1 highlights the spike in the markup residual in 2021-22 and tracks the crest of inflation in both the UK and US. While we did see significant nominal wage growth, particularly in the UK, this growth consistently lagged behind inflation – real pay falling – ruling out wages as the primary driver for the inflation we observed. Additionally, productivity (plotted negatively) captures the pandemic slump and early supply shocks, but its contribution is brief and too small to explain the sustained price surge. The timing and magnitude point instead to firms widening markups during the window of disrupted supply and brisk demand, with margins then easing as conditions normalised. In short: wages and supply shocks mattered, but the dominant component of the post-pandemic inflation episode in both countries is the increase in markups.

Given the evidence, interest-rate hikes were a blunt and insufficient response. You’d think interest-rate hikes might’ve helped. But honestly? They didn’t do much. The post-pandemic surge was driven primarily by supply shocks and opportunistic markup expansion, with a partial, lagging wage-price feedback in the UK. Early in the inflation episode, wage growth trailed inflation, and real pay fell, so a pure wage-push story misdiagnoses the impulse. Even central-bank research cautions that supply shocks should be “looked through” or met with an attenuated response, because they move prices up while pushing activity down, making aggressive hikes a welfare-reducing instrument. Decompositions for Europe and the UK also show profits and margins explaining a sizeable share of the rise, further undermining the case for monetary tightening as the primary remedy. A better mix would have targeted bottlenecks and markups directly e.g., anti-gouging enforcement, transparency on cost-to-price margins, temporary and narrow price interventions in critical sectors, and measures to lift productivity – while using monetary policy more sparingly.

Looking back, it feels kind of obvious that markups were a major part of this – but no one seemed to say it at the time. The monetarist story tells you to blame the money supply and accept the collateral damage of high rates. A wage-push story tells you to blame workers. The more nuanced Kaleckian perspective offers a cleaner match to what you see: in the chaos, many firms just raised markups, profits surged to multi-decade highs, CEOs were spinning around in their office chairs and prices ratcheted upward. Inflation wasn’t just “too much money,” nor just wages or containers stuck at sea. It was also pricing power, exercised.

If the aim is to restore affordability without courting an unnecessary recession, policy must target the mechanism the evidence identifies. This wasn’t about wages. It was a profit-push, plain and simple. And if we’re serious about fixing it, we need to ditch the hammer and pick up a scalpel – smart, targeted stuff like margin transparency, anti-gouging policies and investment to boost productivity – leaving interest-rate policy as a backstop rather than it being the first resort. Unless we tackle markups head-on, prices won’t come down – and let’s be honest, it’s not happening any time soon.