On the 4th of December 1928, while Louis Armstrong’s trumpet sang a tune of national exuberance, President Calvin Coolidge strode into Congress with unwavering assurance, announcing, ‘No Congress of the United States ever assembled, on surveying the state of the Union, has met with a more pleasing prospect than that which appears at the present time.’ He then continued: ‘We have substituted for the vicious circle of increasing expenditures, increasing tax rates, and diminishing profits the charmed circle of diminishing expenditures, diminishing tax rates, and increasing profits. Four times we have made a drastic revision of our internal revenue system, abolishing many taxes and substantially reducing almost all others. Each time the resulting stimulation to business has so increased taxable incomes and profits that a surplus has been produced. One-third of the national debt has been paid, while much of the other two-thirds has been refunded at lower rates, and these savings of interest and constant economies have enabled us to repeat the satisfying process of more tax reductions. Under this sound and healthful encouragement the national income has increased nearly 50 per cent, until it is estimated to stand well over $90,000,000,000. It has been a method which has performed the seeming miracle of leaving a much greater percentage of earnings in the hands of the taxpayers with scarcely any diminution of the government revenue. That is constructive economy in the highest degree. It is the cornerstone of prosperity. It should not fail to be continued.’ [4] Though he hailed a ‘seeming miracle,’ the only real miracle that was being performed was Wall Street’s disappearing act – which would plunge the country into the Great Depression by 1929.

Decades later, Ben Bernanke, former Chair of the Federal Reserve (FED), would attribute the Great Depression to weak monetary policy and put blame upon the FED for failing to inject sufficient liquidity into the economy. He would then address Milton Friedman & Anna Schwartz at Milton’s ninetieth birthday party in 2002, concluding his speech as follows, ‘Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.’ [2]

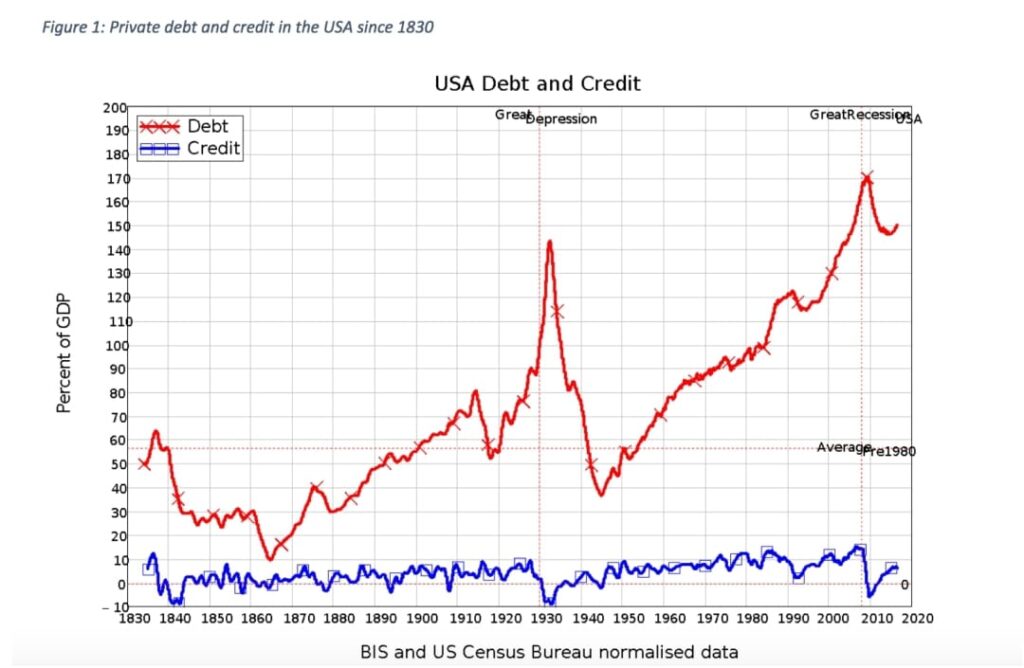

Five years later, after Bernanke declared ‘we’re very sorry’ for the FED’s mistakes that caused the Great Depression, the 2007 – 2008 financial crisis exploded under his leadership. So much for ‘we won’t do it again.’ This, to me, deftly underscores the heart of the dilemma plaguing modern macroeconomics: an almost obsessive devotion to interest-rate fiddling – rather like adjusting a piano’s keys while ignoring the cracked soundboard – thereby overlooking the role of credit and other key performance indicators in driving economic growth. This is not to say that the interest rate is not important, but solely focusing on this aspect of the economy in isolation is naive and overlooks other crucial dynamics. The importance of credit and debt within the economy is paramount to understanding and predicting economic downturns, and this is illustrated by the data below.

We can see from the data by following the blue line that credit in the USA was negative in three separate regions. With all three regions corresponding to the three great financial crises of the past two centuries: including, ‘The Panic of 1837’, ‘The Great Depression’, and ‘The 2008 Financial Crisis’. Negative credit practically, just means that the private sector is paying off more debt than it is borrowing – which

to anyone who loves personal finance would seem like a great thing – except this neglects credit’s role for businesses where additional borrowing can deliver the spark a business needs to thrive, enabling growth and injecting additional vitality into its operations. New home buyers also leverage credit when climbing onto the property ladder which can provide additional economic opportunities for families, further accelerating aggregate demand. I believe it is highly important to accentuate these almost trivial points when referring to the utility of credit in the micro and macro, as these points are largely abstracted away by Neoclassical mainstream economic thought.

The reason credit is ignored is actually due to the money creation problem in economics. The way students and economists are taught to think about money is via Fractional Reserve Banking (FRB) and The Money Multiplier which is the theory that outlines the Neoclassical view on money creation. To explain this briefly, we assume $1000 is introduced into a model economy. The government then sets a reserve ratio

‘rr’ which indicates the proportion of money the bank must hold as reserves. The bank is then free to lend the remaining money out in the form of loans. We then assume that the capital on loan ends up in another bank which again must hold the same proportion of reserves. Given the reserve ratio is set at 20%, Bank 1 will hold $800 in loans and $200 in reserves, and Bank 2 will hold $640 in loans and $160 in reserves and so forth for Bank 3 ad infinitum. This multiplies the initial money that was injected into the economy and the total money supply is said to be equal to $5000 in this specific example. However, this core economic doctrine is incorrect. Two of the largest central banks in the world, The Deutsche Bundesbank [3] and The Bank of England [6], have outwardly stated that this theory is categorically false. The Bank of England states: ‘Money creation in practice differs from some popular misconceptions – banks do not act simply as intermediaries, lending out deposits that savers place with them, and nor do they ‘multiply up’ central bank money to create new loans and deposits.’ [6] The Bank of England directly challenges the theory of FRB; however, Neoclassical economists have politely ignored them by continuing to work under the aegis of the FRB foundations. Neoclassical economists are actually correct in ignoring credit as ‘redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors)’ [1] mathematically, as under this framework this ‘should have no significant macroeconomic effects.’ [1] Nevertheless, by ignoring The Bank of England, this argument is completely flawed and ignores the reality of how money is actually created – via credit issuance – where credit positions itself more centre stage. Even in 2023, the esteemed economics textbook author Greg Mankiw continues to be a proponent of teaching FRB where he believes it to be the only way to explain inflation in the medium run despite its controversy. [5]

Under the mentorship of Professor Steve Keen, under whom these arguments were initially proposed; the utter absurdity of this discipline has been revealed to me. Unfortunately for economics, we have only merely opened Pandora’s box to its ideological worship of monetarism and rational expectations. Economic theories can dazzle with their sleek mathematical elegance; yet, that same brilliance can lull us into a

hypnotic dogma built on assumptions that, when scrutinized, verge on the downright fantastical. Unlike Coolidge’s surpluses, which ’should not fail to be continued,’ the current economic dogma most certainly must not remain unchallenged. To move forward, economists must establish a secure foundation based on the endogenous realities of credit-driven money creation – not the illusory sophistication of textbook theories, but the messy, vibrant realities revealed in history.

References:

[1] Ben S Bernanke. Essays on the great depression. page 24, 2024.

[2] Ben S Bernanke. Remarks by governor Ben S. Bernanke: At the conference to honor Milton Friedman, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois November 8, 2002. November 8th 2002.

[3] Deutsche Bundesbank. The role of banks, non-banks and the central bank in the money creation process. Monthly Report, 69(4):13–34, 2017.

[4] Calvin Coolidge. Sixth annual message. December 4th 1928.

[5] N. Gregory Mankiw. The importance of teaching fractional reserve banking.

https://gregmankiw.blogspot.com/2023/04/the-importance-of-teaching-fractional.html, 2023. Published on Greg Mankiw’s Blog, April 5, 2023.

[6] Michael McLeay, Amar Radia, Ryland Thomas, et al. Money creation in the modern economy. 2014.